This Week In Ag #119

Ushered in by the USA Olympic hockey team’s “Miracle on Ice” and the flight of the space shuttle, Americana was running wild. The decade of excess featured a soaring stock market, booming GNP, and iconic movies and fashion. This was the era of Yuppies… the age of video players… when MTV actually played videos. The 1980s were totally awesome, for nearly everyone but farmers.

The early 80s marked a low point for the ag industry, ranking alongside the Dust Bowl and Great Depression in terms of despair. In 1984, farm debt hit historic levels. Farm income sank to its lowest level in modern history. That happened to be the year I graduated from high school, and it’s why I don’t farm full-time today.

How bad was it? John Cougar Mellencamp recorded the anthem “Rain on the Scarecrow” as a plea for farmers’ plight. He teamed with Willie Nelson to start Farm Aid concerts. Over a quarter-million farms were lost to foreclosures. The Farm Credit system required a government bailout. John Deere laid off 40% of its workforce. Suicide among farmers reached unprecedented levels.

So what caused the 1980s farm crisis? For answers, you need to look back a decade prior. During the early 1970s, the farm economy was booming. New global markets were opening, and farmers were encouraged to plant fencerow-to-fencerow, which boosted production. Soybean prices increased by nearly $10 per bushel in just four years and hit historic highs that weren’t seen again for three decades. Advancements in machinery and crop inputs further enhanced production. Farmland values grew by over 10% annually. Life was very good on the farm.

Until it wasn’t.

In the mid-1970s, an energy crisis sent inflation soaring to a record 14% by decade’s end. With it came towering interest rates that would hit 21%. Compounding this financial disaster, the US imposed a grain embargo on our largest customer, the Soviet Union, over their invasion of Afghanistan. As many farmers expanded in the early 1970s, they took on additional debt to purchase land, buildings, breeding stock, and equipment. For most farmers, land is their biggest asset, often followed by equipment. Farm balance sheets usually grow stronger as land and used equipment prices rise. But in the early 1980s, land prices fell by 60%. Commodity prices collapsed due to high supplies and reduced demand, thanks in part to the embargo and strong US dollar. Input costs rose. It was the perfect storm. Total farm debt doubled in just six years as farm exports dropped sharply. One in three farms were unable to pay their bills. This sent a ripple effect across rural communities, greatly impacting equipment dealers and ag lenders.

Desperate for a solution, the government implemented supply-control measures. The most famous was in 1983, when the USDA borrowed a page from the 1930s New Deal playbook and implemented the Payment in Kind (PIK) program that paid farmers to place land in “set aside” and not grow crops on it. Over 78 million acres were taken out of corn, wheat, sorghum, rice, and cotton production that year. The 1985 Farm Bill instituted a dairy herd buyout that reduced dairy farms by 10% and introduced the modern-day Crop Reduction Program that voluntarily removed marginal acres from production and into soil-saving, environmentally friendly habitats. Supply-reduction programs remained in place throughout the decade and into the 1990s. They had little effect on commodity prices (save for the drought year of 1988), but the series of government payments did help improve farm income.

Eventually, it was demand-creation that helped stabilize the farm economy, from increased international trade, the biofuels boom, and innovative new uses for commodity crops. Stronger and more organized efforts from the commodity association played a key role. In addition, the biotech boom of the 1990s added much greater efficiency to the farm.

So… you may be thinking, with today’s low commodity prices coupled with high input costs; layoffs at equipment makers and big ag; higher than desired interest rates; and geo-political tensions with Russia, China and the Middles East, is the farm sector headed for a repeat of the 1980s (albeit without the great music)?

Not according to farmer sentiment, which just hit its highest level in four years. Sentiment has nearly doubled since last fall, indexing at 158. Other factors suggest we likely won’t go Back to the Future.

For starters, farmland values remain at historically high levels. Based on unique market conditions (including an influx of non-traditional investors who are pushing up prices), land is likely to remain high or at least stable, even against current interest rates. This should help keep balance sheets and keep net worth in order.

In the 80s, variable interest rates accelerated debt levels. Now, most loans are at fixed rates. Since 75% of farm real estate loans are tied to fixed rates, and most are at low rates, overall farm debt should not see such a dramatic increase.

The trade outlook is positive. The Purdue Ag Economy Barometer reveals that 52% of producers expect US ag exports to increase this decade, up from just 33% last month.

Biofuels continue to boom. We’re projected to continue double-digit growth this decade as the demand for cleaner-burning fuels increases and the EV market flattens. Export markets for biofuels keep expanding. Sustainable aviation fuels, driven by the private sector, offer a new and exciting frontier.

Yes, the world’s greatest profession, and the industry at large, is currently facing a host of challenges. But we are far better equipped to meet them than when Marty McFly boarded the DeLorean.

Related Posts

BHN Hosted Annual Staff Meeting and Awards Night in Arizona

Bio Huma Netics, Inc. (BHN) hosted its annual staff meeting on December 14-15, 2022, at its headquarters in Gilbert, Arizona. BHN staff from New Mexico, Mexico, and Brazil also flew in to attend the two-day event. The company planned the all-staff gathering to recognize employees’ contributions and to celebrate significant milestones achieved in 2022—including the

This Week in Ag #52

What are farmers doing during these cold winter days? If they farm in the Midwest, they may be laying tile. I realize this may be a foreign concept to my friends in the west, but in many areas of the Corn Belt, you must often move water out of your fields. In heavier soils, excessive rainwater can remain

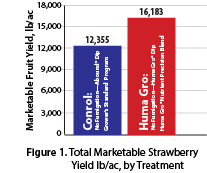

Univ. of Calif.: Huma Gro® Increases Strawberry Yields 30%

Huma Gro® Ultra-Precision™ Blend Plus Root Dip Increases Strawberry Yields 30%, Univ. of Calif. Conducted by: Surendra K. Dara, PhD, University of California Huma Gro® Products: Ultra-Precision™ Blend; plus root dip of Breakout®, Promax®, Vitol®, and Zap® OBJECTIVE The purpose of this research project was to evaluate how a special blend of fertilizer solution and