This Week In Ag #116

“Any corn plant that doesn’t emerge within 12 hours of others is a weed.”

Immortal words from an immortal farmer. My friend Steve Albracht. The brash Texan certainly had a way with words. And with corn.

I called him the Ric Flair of corn growers – he held as many National Corn Growers Association (NCGA) yield contest titles as Flair has wrestling championships. And he was just as bold. Visiting his Hart, Texas, farm was akin to visiting that of Francis Childs or Roswell Garst.

Fast, uniform crop emergence and singulation weren’t just a goal; it was his obsession. He wanted every plant in the entire field to emerge within eight hours.

Studies show that plants emerging 24 hours later can lose up to 25% of their yield. While some corn hybrids may be called racehorses, they don’t close on each other like racehorses do. Slow emergers and runt plants will never catch up to early risers.

Want proof? Find a short corn plant in the field, tie a ribbon on it, and watch it progress. It will never catch up. It may not even make an ear. But it will absorb water and nutrients throughout the season. That’s why Steve called them weeds.

Some years ago, I conducted a survey at Commodity Classic. It revealed that 55% of growers believed emergence was the time when farmers can lose the most yield.

So, how does a farmer help ensure uniform emergence?

Maintaining proper seed-to-soil contact is critical. That starts with the planter. It’s the most important tool a farmer owns; not something you just hook on, pull out of the shed, and go. Successful farmers painstakingly spend hours, even days, carefully inspecting all blades, brushes, bearings, and components to ensure they are in proper working condition and properly lubricated.

Soil conditions play an equally key role. Planting when it’s too wet can plug equipment and drop seeds out of the target zone or lead to surface compaction that stymies emergence. Planting too deep can also impact emergence.

Of course, catching timely rain (or irrigation) right after planting is helpful, too.

There’s also a variety of products that can improve emergence. Seed treatments can protect against pests and diseases. Starter fertilizers and biostimulants can manipulate plant hormones and accelerate root growth. Soil activators and organic acids can stimulate soil microbes.

Time and attention to planting to ensure uniform emergence cannot be overstated. It’s a convergence of talent, skill, and effort; both a science and an art. And nobody did it better than Steve Albracht.

Whenever I scout young corn, I look up to the sky, smile, and hear his famous words.

My corn is now up, having emerged in seven days. This was slower than previous years, due to a lack of GDDs.

At 10 days (photo below), the stand looked uniform. It does show some yellowing, but the soil has remained wet, sunlight has been scarce, and temperatures have been below normal. But all things considered, it looks pretty good.

Due to persistent rains this month, we had a very short planting window. Without the ability to apply in-furrow, Acuron herbicide and nutritionals were applied three days after planting.

That’s when we applied a Huma cocktail that included Zap and X-Tend to accelerate microbial activity, calcium to boost plant strength, sulfur to promote plant vigor, and Breakout to stimulate hormonal activity, along with macros and micros. Root mass is developing nicely.

Related Posts

Bio Energizer® Reduces Cost and Turbidity in Paperboard Lagoons

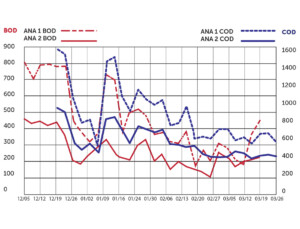

A paper mill wastewater facility was treating 940 tons of paper bags, recycled linerboard, and corrugating medium, daily. The mill was interested in improving wastewater operating efficiency and lowering operating expenses over their standard polymer usage. The plant was experiencing filamentous bacteria, solids, and bulking issues in the final clarifier. It was discharging 4,000 pounds

Fred Nichols’ Insights on Microbiome and the Biologicals Boom

Recently, CropLife interviewed several industry experts, including Huma’s Chief Marketing and Chief Sales Officer, Fred Nichols, to discuss the rapid growth of biological products in agriculture, including biostimulants, biopesticides, and biofertilizers. Fred answered important questions about the microbiome’s role in soil health, industry’s understanding of it, and the new innovations being developed for sustainable farming.

New Video: 8 Essential Products for Wastewater Bioremediation

n this video, Heather Jennings, PE, Director of Probiotic Solutions®, provides an introduction to 8 essential products for wastewater bioremediation.