Experts say that utilizing the smallest nutrients can unlock the greatest potential.

By Larry Cooper, with Dr. Rita Abi-Ghanem

Micronutrients play a critical role in plant vigor, yield, and harvest quality. Yet, they are often overlooked when growers develop their nutrient programs. In this article, we provide an overview of what micronutrients are, the roles they play, how availability is affected by soil and other conditions, how to recognize deficiencies, and the important steps to take when developing a micronutrient plan for your crops.

Science has identified 17 essential nutrients for healthy plant growth. Water and air normally provide the three most important: carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. The rest are generally expected to come from the soil. We are all familiar with those six nutrients required in large amounts (macronutrients and secondary macronutrients): nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. There are also eight nutrients required in smaller amounts (boron, chlorine, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, and zinc), dubbed micronutrients—as well as several elements that have been identified as non-essential, yet beneficial plant micronutrients such as cobalt, silicon, selenium, vanadium, etc. Micronutrients are often treated as an afterthought, though. Don’t sweat the small things, right?

Wrong! Smaller doesn’t mean less important. In fact, in many ways, micronutrients hold the key to how well the other nutrients are used and how well the plant grows, develops, and yields.

What Micronutrients Do

Micronutrients are known to play many complex roles in plant development and health. These include photosynthesis, chlorophyll synthesis, respiration, enzyme function, the formation of hormones, metabolic processes, nitrogen fixation and reducing nitrates to usable forms, cell division and development, and regulation of water uptake. Micronutrients promote the strong, steady growth of crops that produce higher yields and increase harvest quality—maximizing a plant’s genetic potential. In particular, their presence can have a great impact on root development, fruit setting and grain filling, seed viability, and plant vigor and health.

Micronutrient deficiency or toxicity can result in stunted growth, low yields, dieback, and even plant death. Micronutrients also benefit plants indirectly by feeding the microorganisms in the soil that perform important steps in various nutrient cycles of the soil-plant root system.

Of course, the end product is the role micronutrients play when the harvest reaches the table. Increasing evidence indicates that crops grown in soils with low levels of micronutrients may not provide sufficient human dietary levels of certain elements, even though the crops show no visual signs of deficiency themselves. These unseen deficiencies can readily be found through proper laboratory analysis, which we discuss below.

Micronutrients and Soil

Micronutrients occur naturally in soil minerals, which gradually break down from rock minerals and release in forms that are available to plants. Some micronutrients are re-introduced to the soil during decomposition of organic matter from plants and animals.

A critically important concept related to micronutrients is that of their availability to plants. Micronutrients can sometimes be present in soils but not in a chemical form that roots are able to absorb. Soil physical characteristics and environmental conditions play key roles in determining when and how available soil nutrients—especially micronutrients—are to plants.

- Acid leaching can remove micronutrients from the soil, as can intensive cropping—in which large amounts of plant nutrients are removed in the harvest.

- Excessive use of phosphate fertilizers can diminish the availability of some micronutrients, particularly iron and zinc.

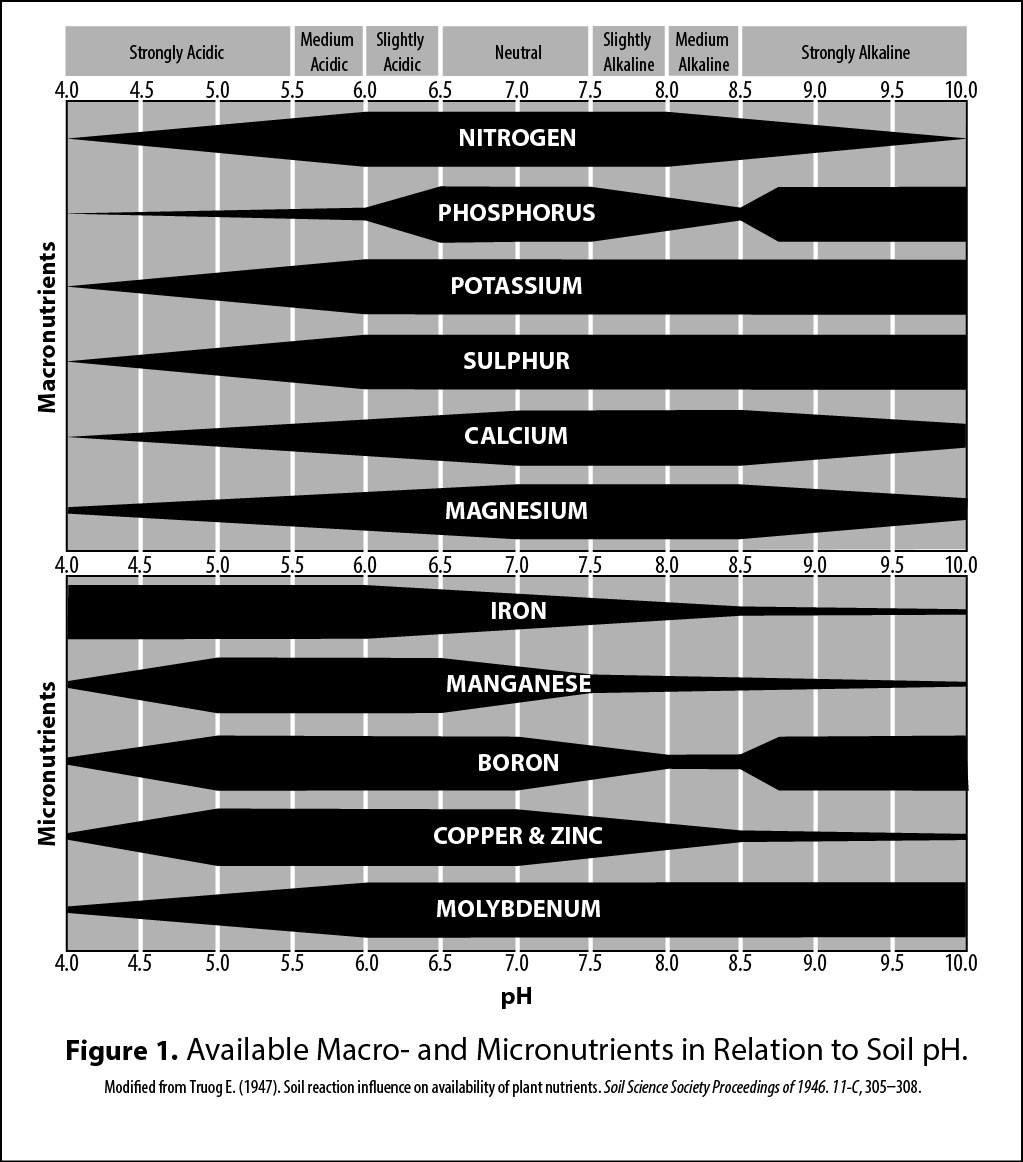

- Extremes in soil pH can result in reduced micronutrient availability (Figure 1) or even cause micronutrient toxicity. Most plants have a pH range “sweet spot” in which the micronutrients in the soil are soluble enough to satisfy plant needs without becoming so soluble as to become toxic.

- Soils very low or very high in organic matter or with sandy texture or heavy clay can result in micronutrient imbalance.

- Soil erosion can carry away humus and organic matter in which some micronutrients are held.

- Cold, wet soils can result in slowing or stopping plant root development; thus, roots explore smaller areas and take in an insufficient amount of micronutrients.

Common Micronutrient Deficiencies

Some crops and soil types are more prone to certain types of micronutrient deficiency than others: examples include boron deficiency in alfalfa; copper deficiency in wheat, corn, and soybeans; nickel deficiency in pecans; and molybdenum deficiency in soybeans. Zinc deficiencies frequently occur on calcareous, high-pH, sandy texture, high phosphorus, and eroded soils. Poorly drained soils may also be deficient.

Some of the more common symptoms to look for include stunted growth; delayed maturation; yellowing and wilted leaves (particularly younger leaves); thickened, puckered, curled, or brittle leaves; dead growing points; aborted flowers, heads, or seeds; poor grain filling; fruit deformities; and increased root disease. These symptoms often occur in irregular patches within fields and can have a drought-like appearance. Keep in mind that there can sometimes be a “hidden hunger” for micronutrients present, in which crops don’t show any overt symptoms until decreased yields are observed at harvest.

Tissue Testing and Soil Testing

While visual symptoms and suspect soil conditions can raise the possibility of micronutrition deficiency, the best approach to identifying a problem and implementing a viable solution lies in regular tissue and soil testing. Your local lab or extension office can guide you through the process but be aware of the strengths and limitations of each.

Soil testing can only measure the number of nutrients identified as present through analytical methods, not their total levels nor their availability to plants. By combining annual soil testing with regular plant-tissue analysis, you can create nutrient ratios providing a much more accurate diagnosis of deficiencies that may be present and the best prescription for addressing those deficiencies. Timing is also an important element. Testing during early to mid-season plant growth can give you time to correct a problem, whereas tissue samples taken during later stages of growth are good to determine corrective actions for the next crop.

If you are dealing with a suspected problem, take plant and soil samples from both the affected areas and the unaffected areas. A comparison of results can help create a much clearer picture of the problem and the actions that should be taken.

4Rs of Nutrient Stewardship

Once the need for a micronutrient supplement has been determined, the next steps are clearly identified by the industry standards set out in the 4Rs of Nutrient Stewardship. These include determining the “Right Source” for supplying the target nutrient, applying the “Right Rate” for optimal benefit, at the “Right Time” of application during the day, growth stage, or the growing season. A detailed discussion of those three Rs is beyond the scope of this article; however, we will further expound on the fourth R, “Right Place,” which addresses the application placement and method.

Micronutrient needs vary with the type of soil, crop planted, available nutrient source, and whether or not the crop is irrigated or on dry land. For more specific recommendations, review resources that apply to your locale and discuss your test analyses with your county extension office and your fertilizer retailer. It is important to find the best micronutrient solutions—including the correct amounts and application timing—to help you reach a complete and healthy balance of all the essential nutrients needed for vigorous crop growth and optimal yield.

For more information or a free consultation, contact Huma® at 1-800-961-1220.

This article was originally published in the March 2015 and February 2016 issues of CropLife Magazine. Read the entire article here.

Related Posts

The Road to Sustainability

“Sustainability is a way of thinking: At Huma® we’ve been thinking sustainably for over 50 years.” We make that statement at the top of the Sustainability section of our Huma® Website. And we stand by it. But what, exactly, does it mean? Over the past 50 years, we at Huma® have always striven to create products that work with nature in support of the well-being of our planet and our customers and to create a working environment that supports the well-being of our staff members and their families. We were doing this long before sustainability became the “thing” that it is now.

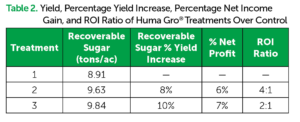

Recoverable Sugar of Sugar Beets Yield Increased Using Huma Gro® Program

Materials and Methods This trial on sugar beet (Beta vulgais) was conducted in Homedale, Idaho by SRS Farms & Crop Services. The crop was seeded on April 18 and was harvested on October 18. A basic grower’s standard fertilizer program was applied to all plots (300 lb/ac made up of MAP 11-52-0, potash 0-0-60, Tiger

Nutrition-based Plant Growth Managers

Maximum Yield without Synthetic Hormones The HUMA GRO® plant growth managers are ideal for stimulating the plant to produce its own beneficial hormones naturally. This helps you deliver improved crop quality and yields, resulting in more uniform maturity and consistent size. The result is greater efficiency, productivity and profitability at harvest. Below are three featured