By Richard Lamar, PhD

Director of Humic Research

Bio Huma Netics, Inc.

To review, the operational definitions of HA and FA are that FA are soluble in water under all pH conditions, while HA are soluble in water only under alkaline conditions. Thus, in a strong alkaline extract, such as Huma Pro® 16 (with a pH of 11.0–12.0), both HA and FA are soluble, primarily because they become salts (e.g., potassium salts), are fully negatively charged, and the negatively charged molecules separate and repel each other. If the pH is decreased to pH 1, for example with concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), all the COOH and Ar-OH groups become re-protonated (i.e., an H atom is added to the negatively charged COO– and Ar-O– groups) and the HA precipitates because there are no longer any negative charges to repel HA molecules, and it is no longer water soluble.

FA molecules, which possess abundant COOH and Ar-OH, as well as other oxygen-containing functional groups, remain in solution because the presence of all these groups makes H-bonding with H2O possible. Conversely, HA molecules, which possess limited numbers of oxygen-containing functional groups that do not possess enough force via H-bonding compared with the size of the molecules to keep the molecules soluble, become more hydrophobic (i.e., H2O repelling). As a result, HA molecules start to form hydrophobic aggregates, which ultimately results in their precipitation. So, when Huma Pro® 16 is added to a highly acidic fertilizer (e.g., Super Phos®), the HA precipitates and is likely to clog spray nozzles. [See our video on Mixing Liquid Humic Acids with Agrochemicals.]

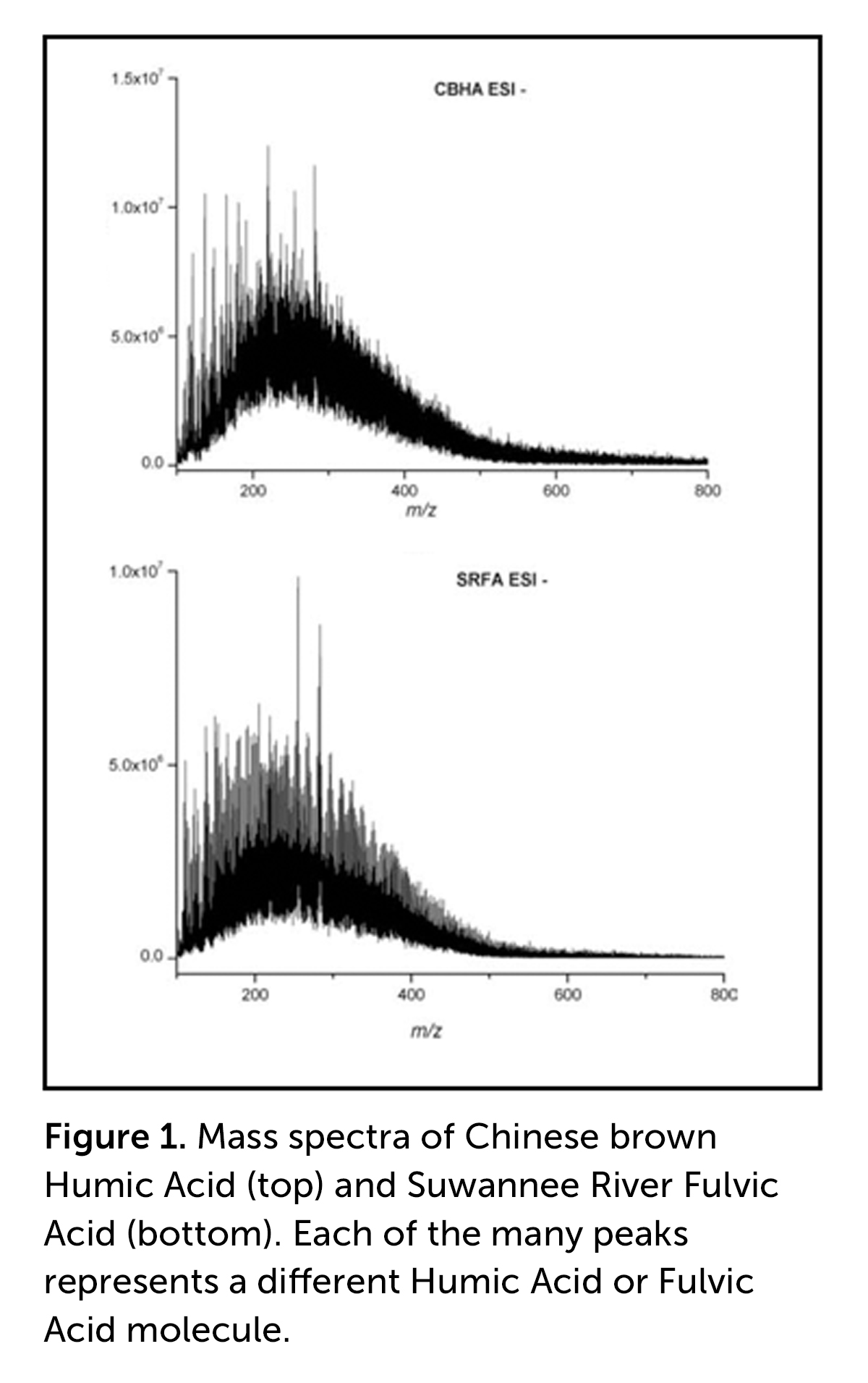

The take-home message is that HA do differ from FA, but not because of their relative molecular size. They primarily differ because FA molecules contain higher numbers of oxygen-containing functional groups, which allow them, through hydrogen bonding, to remain water soluble even at strongly acidic pH values.

Related Posts

Cherry Blossoms: A Sight to See

Cherry Blossoms: A Sight to See! Konnichiwa! This Week in Ag comes to you this week from Japan. I’m here for my son’s wedding. My new daughter chose this time of year to align with the famous blooming of the cherry blossoms. These Sakura trees provide amazing backdrops for wedding photos. You may have heard about Japan’s cherry blossoms and perhaps seen pictures online or on travel shows. But let me be clear: these do not do the flowers justice. The sights are awe-inspiring. Gardens, parks, temples, river banks and streets lined with Sakura trees provide spectacularly scenic backdrops. Pedals blow in the wind like gentle snowfall. A unique feature of some Sakura trees is their ability to bloom before leaves emerge, which further emphasizes the flowers.

This Week In Ag #98

Oilseeds are now a lightning rod. America’s top ag export, accounting for over $40 billion, is at the center of a heated debate on the state of America’s health. The appointment of RFK Jr. to head Health and Human Services will do nothing to ground the conversation. He’s been outspoken in his view of how seed oils

The Bearing That Broke the Farmer’s Back

Equipment breakdowns have always been part of farming, but today, the repair bills and downtime can feel unbearable. With parts prices soaring, dealer labor rates climbing, and right-to-repair battles heating up, farmers are feeling the squeeze every time a machine quits.