This Week In Ag #115

What better way to celebrate #NationalStrawberryMonth than by visiting my good friends George & Susan McDonald, owners of Catesa Farms, in middle Tennessee. George says that strawberries are grown with one of two goals in mind: shelf life or taste. He opts for the latter. My taste buds agree – their berries taste too good to be legal!

George does not sell his fresh strawberries to grocery stores. He sells directly to consumers from his farm and to local restaurants. His “grown for taste” philosophy does have a compromise. You need to eat, freeze, or make jam (thankfully, my farm girl wife excels at this) within about three days, because they have little shelf life.

The traditional commercial operations found in California (which produces over 90% of all US-grown strawberries), Florida, and Mexico focus on shelf life for their large retail grocery store customers. Once picked, they typically take about three days to ship across the country and have a shelf life of about one week.

For those concerned with carbon footprints, strawberries are a great example of the need to support local farmer markets and develop local food systems. Not only does locally grown produce offer incredible taste, but it also dramatically slashes freight distances. But there’s no denying Americans love this wedge-shaped red fruit, which on average they consume at a rate of 5.5 pounds per year.

Last year, I planted corn on May 1, and it was up in five days. This year, I planted on May 6 and five days later… still no corn emerged. How could that be? In a word: heat. Or more specifically, the lack thereof.

You see, when it comes to crop emergence, it’s not really about days, but Growing Degree Days (GDD). Soil temperatures must be 50 degrees, and the kernel must absorb 30% of its weight in moisture for corn to germinate (or spout). But to emerge above the 2 inches of soil it’s planted in, corn relies on a heat index called Growing Degree Days. Corn needs about 120 GDDs to emerge.

GDDs are calculated by adding the day’s high and low temperatures, dividing by 2, and subtracting 50 (for calculating purposes, 86 degrees is the maximum, 50 degrees is the minimum). Last year, on the day I planted, we hit 88 degrees for a high and 65 for a low, which gets us 26.5 GDDs. This pattern continued, which brought my corn up on the morning of day 5.

This year, it’s been much cooler. In the first five days since my seeds were planted, we’ve only accumulated 83.5 GDDs. Based on the forecast, I should see corn spike mid-week.

I must admit, since moving to the South, I’ve gotten spoiled when it comes to crop emergence. Usually, an abundance of warm sunny days brings crops up in a matter of days. Back in Illinois, it was not uncommon for corn to sometimes take about two weeks to emerge.

Related Posts

Unique Water Towers That You Should See

By Jael Batty From globes to lighthouses, historical and refurbished water towers around the world are eye-catching landmarks.

This Week in Ag #30

Labor Day signals the end of summer and ushers in the frolics of fall: football, pumpkin spice, UGG boots (well, maybe not in Arizona), hoodies, weenie roasts, and of course, harvest. When do farmers start harvest? For commodity crops, this is largely dependent upon the crop, the variety, geography, and the size of the farmer.

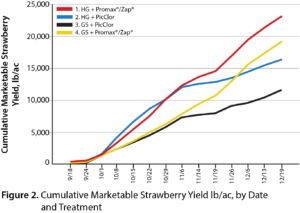

Huma Gro® Nutrient and Fumigation Replacement Program Increases Strawberry Yields 97%

Conducted by: Pacific Ag Research Huma Gro® Products: Ultra-Precision™ Blend (Fresca CA Strawberry Mix), Promax®, and Zap® OBJECTIVE This field trial assessed the effects on strawberry yields of replacing field fumigation with periodic applications of Huma Gro® Promax® and Zap® and replacing a grower’s standard fertilizer program with irrigation-applied Ultra-Precision™ blended liquid Huma Gro® crop